Visiting the 500 year old Portuguese slave trading fort of Elmina on the coast of Ghana, a country through which 10% of the Atlantic slave trade took place, and visiting its hot and oppressive holding cells brought the history of slavery front and center, a legacy whose impact the world still grapples with today.

Visiting the 500 year old Portuguese slave trading fort of Elmina on the coast of Ghana, a country through which 10% of the Atlantic slave trade took place, and visiting its hot and oppressive holding cells brought the history of slavery front and center, a legacy whose impact the world still grapples with today.

The African continent in the last half-millenium had 3 primary slave markets:

1) Africa itself. It is estimated that between one-third and one-half of the populations of African countries lived as slaves to other tribes, an endemic practice throughout the tribe-dominated continent, both before, during and after the European-run Atlantic slave trade. While clearly greatly diminished, there are still remnants of this practice today. In Niger, for example, it is estimated that 8% of the current population remains enslaved.

2) The Arab slave trade. Dominated by North African slave raiders, up to 20 million sub-Saharan Africans were captured and funneled up and sold off in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire.

Interestingly, even Europe was not immune to the North African slave trade: over 1 million Europeans from coastal towns in Italy, Portugal and Spain were captured and sold as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries. Between 1609 and 1616, England alone lost 466 ships to Arab slave traders, and by the end of the 19th century even the United States found some of its ships captured and crew sold off, prompting one of the first wars the U.S. would ever engage in: the two Barbary Wars of the 19th century to combat the slave raiders of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya (the phrase “From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli…” in the US Marines hymn refers to Marine action during the Barbary Wars in Tripoli, Libya).

3) The Atlantic slave trade. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, some 10 million African slaves were shipped off from Africa’s Atlantic coast to the New World. Pioneered by the Portuguese and later by Dutch, Spanish, British and French ocean traders, the vast majority of these slaves (39%) went to Brazil or to British (18%), Spanish (18%) and French (14%) colonies in the Americas. 6.5% went to the United States.

Unlike the Arab slavers, who ventured south to personally raid sub-Saharan African tribal villages, the Europeans for the most part remained confined entirely to a handful of forts dotted along West Africa’s Atlantic coast and relied on an exchange of goods with dominant African coastal tribes to trade for slaves. It was far too dangerous for Europeans to venture inland themselves, both because the tribes that dominated Western Africa would not allow it and also because of the various health hazards (malaria, etc.) for which they were ill-equipped.

Another substantial difference between the Arab and European slave trade is that the Arabs largely favored the export of female slaves, whereas the Europeans were primarily interested in male slaves for farm work on their New World colonies. 70% of slaves to European colonies went to work on sugar plantations, with the rest primarily to the farming of coffee, cotton and tobacco.

Britain was one of the first countries in the world to ban trading in slavery in 1807, largely thanks to the efforts of Quakers and other evangelical Christian groups. The Royal Navy was deployed and tasked around the world to treat slave ships flying under any country’s flag as pirate ships. Between 1807 and 1860, the British West Africa Squadron intercepted over 1,600 slave ships, freeing some 150,000 African slaves.

Britain’s stance was not popular with the dominant tribal kingdoms of West Africa. King Dezo of Dahomey (now Benin) said in the 1840s:

“The slave trade is the ruling principle of my people. It is the source and the glory of their wealth…the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery…”

And the King of Bonny (Nigeria) upon hearing that Britain had outlawed the slave trade:

“We think this trade must go on. That is the verdict of our oracle and the priests. They say that your country, however great, can never stop a trade ordained by God himself.”

While both Britain (and a year later in 1808 the United States) banned the slave trade, it would take several decades for the colonial powers to end the practice itself.

France was the first country to do so, although not from any kind of moral standpoint. France was unable to quell the massive slave revolt in 1791 in its New World colonies and was forced to offer a general emancipation. Napoleon tried to reinstall slavery in 1802, but the French armies were defeated by the former slaves and as a result Haiti became in 1804 the world’s first independent black republic.

Britain outlawed slavery in all of its colonies in 1833, and the United States via the 13th Amendment at the end of the Civil War in 1865 (although it would take another century or so to put an end to systemic discrimination).

In 1847, the West African country of Liberia (for “liberty”) was founded by freed former slaves from the United States. The capital city is Monrovia (named after James Monroe), and its main university is Lincoln University. The flag of Liberia is like the American flag but with one star, and its founding government was modeled after the U.S. Constitution.

Although largely officially abolished both in word and deed throughout the world, racial slavery persists in many places to this day, most notably in certain regions of Africa. Additionally, human trafficking (largely of women and children) has emerged as the new face of slavery and is a serious issue worldwide, with millions forced into either prostitution or as domestic servants.

March 19th,2009

Ghana |

6 Comments

Once in Ghana, I somehow found myself staying in a hut a stone’s throw away from the beach, a great way to unwind after weeks in the dry, harsh desert.

I went into the village in the afternoon, and was informed by a concerned local that it was not safe to walk around with a camera. I thanked him but kept on going. One warning does not necessarily reality make.

On the beach, though, another man flagged me down and, very alarmed, told me the same. Ah. Two identical warnings is different, and I had no intention of testing the three-strikes-you’re-out possibility. Plus I did notice that I was getting some hostile looks. So I calmly put my camera away and simply enjoyed the remainder of the sun sans shutter.

Here, then, are the few images from the beach village of Kokrobite, Ghana (plus a couple shots from a jungle canopy walk in Kakum)

March 18th,2009

Ghana |

2 Comments

I shot through the country of Burkina Faso so fast I’m no longer even sure I was there. Here’s how it happened.

My plan was to cross into Burkina Faso from Mali at the border town of Koro, and from there make my way to the northern Burkina city of Ouahigouya. I had been looking forward to spending a week or so exploring Burkina Faso, as it had been described as one of the most welcoming of the West African countries.

My expectations underwent a dramatic change for the worse in Sevarre, Mali.

First, I met a Canadian woman who had just come from Burkina and had horrible experiences there–she was constantly harassed by men and several times felt quite physically threatened. This only happened to her in Burkina Faso and not in other neighboring West African countries. Well, being a single male traveler is quite different than female, so I wasn’t too concerned, but I filed that away under the “good to know” category.

The next day, I met a German traveler who had also come up into Mali from Burkina. An easygoing fellow, he surprised me by stating how much he had hated the northern Burkina town of Ouahigouya. Exactly where I was headed. Hmmm.

Then I met one of those people that has more stamps in their passport than there are stars in the sky. This guy had been touring West Africa for months, and even insanely went through quite dangerous countries like the Ivory Coast (which regional guidebooks don’t even include for fear that travelers might accidentally go there).

Anyway, in between sharing thrilling travel stories, he mentioned how bad Ouahigouya was, and how he’d gotten a little roughed up there. Uh-oh. When a guy who’s traveled through some of West Africa’s most dangerous countries confirms what other people have already stated, I pay attention.

So the day came for me to make my way to the Burkina border. First, I had to roam through half of the dusty Malian town of Bandiagara to find the truck headed south to Koro. Not a bus, not a shuttle, not a taxi. We’re talking a genuine cargo transport. Not quite like this one, since it had a roof and the cargo area was packed (after the bags of goods) with what felt like 200 people, but similar enough:

As we made our way down the face of the cliff and across the bumpy desert, I actually managed to both bruise and torque my spine. With absolutely no wiggle room and people wedged up on either side of me, a woman sitting on my foot and another guy right in front of me (I kept my hands between my legs out of fear of accidental castration), I was locked in place on the truck for the entire dusty ride, and on particularly rough sections my back would slam into the wooden railing behind me.

The winds of the Sahel and the truck itself flung dust and sand through the back, making it difficult to keep my eyes open, and there was so much flying around that I started feeling sand gritting between my teeth. I now fully understood why desert nomads wrap their entire heads with cloth–good against the heat, and great protection against the sand.

Several hours later, we arrived in Koro, a baking hot trading village lost on the edges of Mali’s southern desert. Want to get a sunburn in less than 60 seconds? Walk around in Koro at noon.

From the cargo truck, I climbed aboard one of these:

Except ours was worse for the wear. The sliding side door kept falling down, and the back door only shut if you slammed it with Herculean might, usually only successful on the 16th or 17th attempt. My bag was loaded on the roof, so that by the end of the trip I could also take back as Malian souvenir about two extra pounds of dust and sand.

The Mali border post was actually two long white dome tents that looked like greenhouses. Flapping away in the wind and coated with dust. The Burkina Faso border, past the circling vultures eyeing our movements across the barren landscape (ugly, ominous birds, vultures), was a small cement square room that included both the immigration officer’s desk and cot. This was followed by a customs check, where our dusty luggage was brought down from the roof rack for stern-looking soldiers to rifle through with the muzzles of their machine guns before being reloaded on the rooftop in such a way as to catch dust and sand from other angles.

Hours later, after everyone in the van had sweat enough to ensure mild dehydration, we arrived in the Burkina town of Ouahigouya. One of those overgrown truck-stop kind of places.

Obviously, given what I’d been told, my goal was to leave immediately. I’d already been traveling for 8 hours, but successfully hunted down a bus leaving an hour later for the capital city of Ouagadougou. Woo-hoo!

As soon as the bus left Ouahigouya, I started to relax. Only 3 hours to go, and I’d managed to both successfully cross the border and avoid staying any longer than necessary in the apparently troublesome town, and I imagined myself already relaxing in the comfort of a pleasant hotel in Ouagadougou.

There were a few surprises left in store.

First, when I got to Ouagadougou and gave the taxi driver the name of the hotel to take me to (apparently the best budget hotel in the entire capital), he dropped me off at the wrong location. In the middle of the city. At night.

A man with a roving eye and a Quasimodo-like feel to him asked me where I was going, and volunteered to take me to the hotel, which apparently was only a couple of blocks away. Reluctantly, I agreed. There were few taxis on the streets, so what choice did I have?

Walking downtown at night in a city can sometimes be disconcerting. Doing so in a city you’ve never been to is more so, and with a backpack on your back yet more. This is when you’re at risk.

When the hotel loomed out of the darkness, I thought there must have been some kind of mistake. This is the best budget hotel in all of Ouagadougou?! Imagine arriving here at night, with almost no streetlights:

Creepy.

But no mistake. This was it. The hotel. The rooms, shuffled along old and dark hallways, painted green cement with the most mysterious collection of stains on the walls, did nothing to warm me to the place. The middle window on the second floor was my room, to be shared with a colony of mosquitoes.

After dropping off my bags, I went down to reception. It was 9:00pm, dark outside but not particularly late. I asked where the closest internet cafe was.

“Just around the corner and down a few blocks,” I was told.

“Great, thanks,” I answered.

“Wait, you’re going now?”

“Yes, why?”

“Well, the bandits…”

“Bandits?!”

“Yes, bandits. Maybe it’s better you go in the morning…”

That’s it, I thought. I’m out of here.

But it took me another 36 hours before I could arrange a bus ticket out, a 19-hour journey from Ouagadougou to Accra, the capital of Ghana.

All told, I spent less than 48 hours in the country of Burkina Faso. Did I short-change the country? Definitely. Do I regret it? No. Be it Ouahigouya or Ouagadougou, you gotta do what you gotta do.

More explorations along the Bandiagara Escarpment (the official name of the 100 miles of up to 1,600 ft. high sandstone cliffs where the Dogon reside). Note that although these villages look empty, they are all well and truly inhabited. Really.

March 16th,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

After seven hours of sweaty trekking through the sand and desert cliffs of Dogon country, we arrived at dusk.

On a rocky plateau, surrounded by a flat expanse of rocky nothingness, stood a small lone table. With a green tablecloth and little mini woven chairs. Strangely surreal. Uncomfortably small.

Next door, what I had thought was a stable were actually the sleeping quarters. The ceiling was a degrading patchwork of long intertwined sticks, caving in in a number of places and so low you had to hunch over to stoop around. Thin foam mattresses lay on the dusty, rocky ground, and looking up you could see the stars through the holes in the patchwork. Or at least through the holes not covered over with a strip of cardboard.

The shower consisted of a bucket of cold water within three chest-high mud brick walls and a curtain blowing in the wind. Great 360 degree view of the scenery from my showering spot and, admittedly, vice versa. I washed in the pitch dark of early evening and then, bereft of towel, waited to air dry, wondering which would kill me first: the surprising chill of desert wind at night or the mosquitoes circling with glee at the sight of all that exposed skin.

After I’d stopped shivering, a dinner of spaghetti and chicken was served and eaten by starlight.

I started gnawing on a chicken leg, but couldn’t pry any meat off of it. Frustrated, I gave up and put it aside, chalking it up to the toughness of desert chickens. I was about to fork the other piece of chicken into my mouth when, by the faint light of the north star, I saw a jagged outline that looked suspicious.

I set my fork and chicken down and fished for my flashlight in my pocket to better illuminate my meal. Well whaddaya know, I’d almost stuffed a chicken’s head into my mouth. That jagged outline I’d spied was that telltale red flap of skin chickens have on their heads. And the other piece that I had taken for a chicken leg was actually the extended chicken’s foot and claw. Wonderful, just wonderful.

I opted to forgo chicken for the remainder of the meal, although one nagging thought kept resurfacing despite my valiant attempts to repress it: could one of the chicken’s eyes have fallen out and still be in my spaghetti? I’ll never know.

At night, the mosquitoes danced and the rocks under my thin foam mattress ensured future prosperity for chiropractors everywhere. In a corner, a miscellaneous rodent gnawed to sharpen his teeth, and in the distance, a rifle shot echoed through the cliffs.

Night in the Dogon had arrived.

March 15th,2009

Mali |

4 Comments

Safe in their cliffside villages, the Dogon tribes resisted Muslim conquest and conversion for centuries, although they were often victims to slave raids.

Even today, despite living in a staunchly Islamic country, the majority of the close to a million Dogon tribespeople continue to practice their animist beliefs.

March 14th,2009

Mali |

5 Comments

Before they slaughtered the cows, there was drumming.

Before they slaughtered the cows, there was drumming.

A group of older women were gathered in a semicircle, banging on large wooden bowls, while others simply clapped along, all of them singing the rhythmic funeral songs.

We were watching a Dogon funeral in the small traditional village of Tiougou. Dogon tribes live in cliffside villages in eastern Mali, a dry, hot, desolate desert landscape carved out of the Sahel.

A prolonged 3-day event, as part of this funeral we’d already been treated to the unmistakable (and mildly disconcerting) sounds of celebratory gunfire throughout the night and into the morning, each loud shot prolonged by its echo bouncing off the desert cliffs.

The Dogon guide turned to me and said: “only women whom the deceased has slept with are allowed to bang the bowls.” Ohhhhh.

I looked at the gathering of Dogon women with much keener interest. A regular Don Juan de Dogon this fellow must have been, although it’s an odd thought to reflect on when most of the women in question looked like respondents to a casting call for “spot your Dogon great-great-grandmother.”

I wondered, too, if this practice led to any awkward moments between some of the women. As in, “what, you too?!” And what of these women’s current husbands? I tried to look for older men glaring from the sidelines, but didn’t see any. Clearly, I was projecting my Western biases on an entirely different culture. But still.

Speaking of which, our guide explained to us some of the marital customs. The parents pick the bride for their son, almost from birth, and they are married around twelve or thirteen. “No” is not an option, as our guide repeatedly insisted (leading me to suspect he may not have been entirely happy with his parent’s choice). Perhaps to make up for this, the husband is allowed to take on usually one but up to three more wives of his choice. And mistresses, of course.

The bride does not immediately move in with the husband. She first has to bear a child, which she then gives to her parents so that it can take her place since she will be leaving. Only when she has her second child does she move in with her husband.

Which, of course, led me to wonder: how does Don Juan fit into all this? As I understood the guide’s answer, until the woman starts to live with her husband, she’s free to explore with others (as is he). And hence the gaggle of women lustily banging away on the bowls for the funeral.

After the banging and the singing, a cow was dragged out to the main square. It was forced down onto the ground, and a Dogon man with a long knife slit its throat. Moving with remarkable efficiency, other men hacked off its horns, chopped off its tail, and skinned the carcass, leaving it to bloat in the mid-day heat.

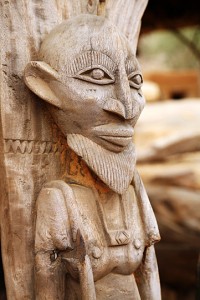

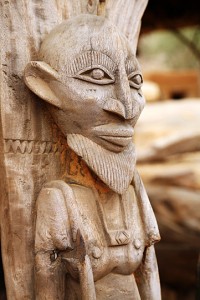

Dancers wearing intricate traditional masks came out and danced around the cow, all of them physically fit men wearing what resembled purple Hawaiian hula skirts of straw and strings of shells across their chests. Masks play a vital role in Dogon culture and the complexities were far too intricate for me to understand, but the rhythmic dancing around the dead cow was mesmerizing and felt entirely appropriate. Later, rifles were fired again as part of another dance.

And with that, a Dogon village bade a final farewell to one of its men.

March 13th,2009

Mali |

8 Comments

One of the oldest known cities in sub-Saharan Africa, Djenne has for centuries been an important trading center, with goods staging in the city for a river trip up to Timbuktu before crossing the Sahara to the ports of North Africa via camel caravans.

Now, its importance is primarily for local trade, with a bustling Monday market serving as outlet for the entire region. And the town itself, with its postcard-famous mud brick Grand Mosque de Djenne, is a UNESCO listed World Heritage Sight.

Yes, the mosque is indeed unique and impressive, but I have to admit that from my perspective, the most surreal and memorable part of the day was the remarkably cramped and uncomfortable journey there and back.

March 12th,2009

Mali |

No Comments

Unlike next-door Sevarre, Mopti is a beehive of market and transport activity. Occasionally overwhelming perhaps, but never a dull moment.

March 11th,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

So I’m casually walking around taking pictures in the Malian desert town of Mopti, as I have in countless other towns in many countries. Here’s one random exchange:

So I’m casually walking around taking pictures in the Malian desert town of Mopti, as I have in countless other towns in many countries. Here’s one random exchange:

Me to guy that looks like Mr. T: May I take your picture?

Mr. T, glaring: If you had taken a picture of me, I would have broken your camera.

Me: I didn’t take your picture. I asked if I could.

Mr. T: I’m telling you, if you had taken my picture, I would have taken your camera and broken it.

Me: I see. I was being polite.

Mr. T: You shouldn’t have even asked me.

Me, laughing: Okay then. Have a nice day.

And this is not an isolated case, nor the most extreme. I’ve had guys come out of nowhere to yell at me as I’m taking a picture of someone else who has agreed to have their picture taken, as if personally affronted that I’m photographing people. Or start screaming that I’m not allowed to take a picture of this building, or this car, or this street.

When possible, I’ve defused these situations with smiles and politeness. Sometimes I’ve had to yell back. And move on.

This is not just about photography, or about being a foreigner. I’ve noticed that verbal aggression is much more common in West Africa than in most other countries. People are quicker to raise their voices, get in each other’s faces, or enter into someone else’s argument uninvited.

Is it cultural? The oppressive heat? Whatever the reason, it makes a day out with the camera all that more interesting, and in some ways it makes me appreciate the photos I return with all the more.

Like the guy in the picture above. He was initially upset that I was taking pictures in “his” street and loudly challenged me from across the street. I smiled, went over to him, shook his hand, introduced myself and we chatted for a bit. By the end of it he volunteered to have his photo taken and posed himself for the shot.

March 10th,2009

Mali |

3 Comments

Visiting the 500 year old Portuguese slave trading fort of Elmina on the coast of Ghana, a country through which 10% of the Atlantic slave trade took place, and visiting its hot and oppressive holding cells brought the history of slavery front and center, a legacy whose impact the world still grapples with today.

Visiting the 500 year old Portuguese slave trading fort of Elmina on the coast of Ghana, a country through which 10% of the Atlantic slave trade took place, and visiting its hot and oppressive holding cells brought the history of slavery front and center, a legacy whose impact the world still grapples with today.

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

Click to subscribe via RSS feed