The desert river port town of Mopti is not particularly popular with guidebooks:

“…reputation for hustlers…old town lacks aesthetic harmony…new town isn’t particularly modern…feels a little crowded and oppressive…odoriferous shores of the port…”

But photographically, how can you go wrong with a town built on three islands (at the confluence of the Niger and Bani rivers) linked by dykes in the middle of desert desolation, whose original settlers were the Bozo tribe of fishermen?

March 9th,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

It’s hot. The whole town is lulled by the scorching heat into a sleepy torpor. Only the dusty Harmattan wind rustles through with an occasional gust of energy. I yearn for shade and a cold drink.

March 8th,2009

Mali |

No Comments

A red sept-places

Sept-places. French for seven-seater.

At some point a decade or two ago, France must have shipped over several boatloads of Peugeot 504 station wagons to West Africa. Maybe they made too many and couldn’t sell them. Maybe the Africans bought them at a volume discount.

Whatever the how of how they got here, the point is that they’re here. By the thousands. Cars so old and beat up you wonder how they could have survived such abuse, and are even more shocked when they not only properly start but actually sputter away after a grinding of gears. 200,000 miles in the desert? 400,000 and still kicking? It’d be a great commercial for the Peugeot car company, if these beat-up relics didn’t look so incredibly ugly.

They are called sept-places because, apart from the driver, they can carry seven passengers. One in the passenger seat, three cramped in the middle row, and three even more cramped in the last row. The counting of seven does not include young children or miscellaneous personal effects, nor does it account for women of unusual girth. When one practically sat on me the other day to fit inside the car, I seriously contemplated whether I’d be better off walking to the town 30 miles away. Someone had to shove the door closed from outside.

But they work. Despite having the appearance of rolling scrap-heaps (and the one pictured above is by no means a sorry example–it looks in much better condition than many others I’ve seen), these short and mid-distance shared taxis dutifully ply the roads of West Africa, braving elements and conditions that would put most cars out of service within a week.

And on the plus side, I’ve learned quite a bit about the anatomy of cars. I now know, for instance, how a door handle works, having seen its entire mechanism crudely and blatantly exposed to the light of day. I also know that cars really don’t require all their parts to function. Just enough seems to work just fine.

Oh, and while they’re called sept-places and in the Senegal this is widely respected, in Mali they’ll shake their heads and laugh. It’s really a nine-places, they say with a grin. Two more for the road.

March 7th,2009

Mali |

No Comments

Roaming the dusty streets of the desert town of Sevarre:

March 6th,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

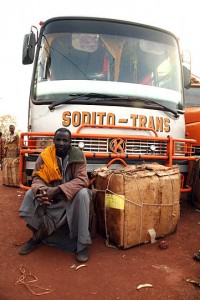

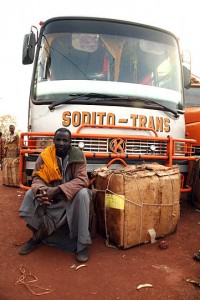

This bus has a plow, I realized.

This bus has a plow, I realized.

A brush guard, actually, but mean enough that it’s clearly not just for show. All the buses have them, and they’ve definitely seen action. Wandering livestock beware!

The 8:00 bus from Bamako to Mopti left only an hour late, and I’m told that’s actually pretty good. Packed, of course, and I soon realized that bus travel in Mali is different than in other places.

At the Bamako city limits, the bus stopped to cross the police checkpoint. A number of touts got on, both via the front door and the middle-rear ones, hawking their wares. Water! Biscuits! Fresh papaya! Sesame bars! Cakes! Nuts! The bus may have been full before, but now the vendors’ mass edged in to accompany their shouting, and the bus was one big loud swarm of full.

Suddenly, authoritative yelling from the front, followed by a loud snap. As one, the vendors from the front launch themselves towards the rear, a panicked mass of fleeing salesmen.

One of the bus’ “enforcers” had his belt in his hand, whipping the closest vendor across the back. Not a casual slap. As hard as he possibly could, yelling and cursing at the same time. Anyone who felt that belt didn’t just get a nice red welt—they got bloodied.

I don’t know what the vendors did to piss this guy off, but they fled towards the back doors with incredible haste, and what a second ago had been an aisle full of hawking salesmen almost instantly dissolved into just one angry bus enforcer with his whip of a belt. Satisfied, he turned around and sat down. Maybe he was having a bad day.

Bamako may be a city baked into the earth, but in that case the rest of Mali is the oven. Hot, dry, dusty desert. No air-conditioning in the bus.

We drove for 11 hours through the desert, the bus doors open to (thank God) help ventilate. By the time we arrived, I’d lost my sense of color. No more greens, blues or yellows. Only monochromatic shades of tanned dust. The roads, the flat landscape, the shrubs, the houses, and even the trees: all uniformly dust-colored. And when I looked at myself in the mirror, so was I. Coated in a fine, gritty layer of desert dust.

No dead cattle, though. At least there’s that.

March 5th,2009

Mali |

1 Comment

Some wanderings through Bamako’s city streets. You’ll have to mentally add the glaring sun and oppressive heat.

March 4th,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

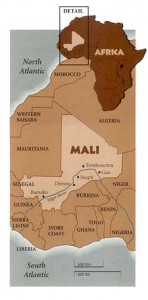

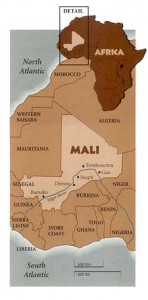

Mali is an interesting country, and not just because it is shaped like a lopsided butterfly.

Mali is an interesting country, and not just because it is shaped like a lopsided butterfly.

Once the seat of the aptly named Mali Empire of the Middle Ages and briefly under French colonial rule from the end of the 19th century until its independence in 1960, Mali is home to both a diversity of culture and landscape that make it a unique place to visit.

Comprised of a variety of ethnic groups, from the famed and feared Tuareg desert nomads of Timbuktu in the north to the unique Dogon cliff dwellers in the southeast, Mali also geographically straddles the 3 main African climates: Sahara, Sahel and Savanna.

This satellite map of Mali provides a useful visual reference:

You can see clearly see the desert nothingness of the Sahara in the north. With very few exceptions (the Tuareg being one), nobody actually lives in the desolation of the Sahara. And in the south, the greenery of subtropical savanna. The patch in the middle running along the southeast part of the country, which forms the transition between the two, is called the Sahel, a narrow strip crossing the entire continent of Africa:

Unlike the Sahara, the Sahel is livable. Although, frankly, not easily. Or comfortably. Transition it may be, but it looks and feels like the Sahara to the uninitiated during the dry season: desertlike and unbearably hot throughout the year. The difference is that the Sahel does get some rainfall during Africa’s wet season, and thus shrubs, farming and some seasonal rivers and irrigation is possible.

Subtropical savanna (grasslands with scattered trees) starts directly below the Sahel, from suspiciously sandy and desert-like next to the Sahel to progressively greener and lusher the further south one travels. On the eastern part of the continent, for instance, most have heard of the famed savanna grasslands of the Serengeti.

Adding flavor to all three climates is the Harmattan, strong trade winds that blow south out of the Sahara from November to March. Varying in intensity daily and even hourly, these winds carry fine particles of dust (and, when stronger, actual sand) that create the effect of a light haze to outright heavy fog, covering all in its path with dust and sand.

During this winter season, I was surprised to discover that the Harmattan haze completely swallowed sunrises and sunsets. In the mid-afternoon, even on a completely cloudless day, the sun would simply dissipate into the Harmattan haze and a slow progressive dusk would overtake until the darkness of actual sunset several hours later.

Harmattan haze at my side, it’s time to venture forth deeper into the Sahel.

March 3rd,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

Street photography in Africa is much different from southeast Asia and India. A little more hostile, and a lot more aggressive. Several times I’ve had to get myself out of heated exchanges with folks who did not at all appreciate my snapshots, no matter how good the image. Kind of reminds me of how Pascal and I got mobbed by angry photographees on our first day in the Congo a few years ago and hauled off to the local police station.

That said, most people are genuinely friendly. But see if you can guess which of the pictures below almost got me into a physical altercation…

March 2nd,2009

Mali |

2 Comments

There is a scam as old as travel itself.

There is a scam as old as travel itself.

As soon as you arrive at your destination, as soon as you exit the cocoon of the airport, or the confines of your train, or arrive at the dock, the throngs are waiting, eager to pounce. Fresh meat.

You’re tired, possibly exhausted, nearing the end of your journey. You’re in an unfamiliar town. All of your travel belongings are on your back or in your hand—your moment of greatest vulnerability.

And so you press through the throng of touts and taxi drivers and who knows who else, you yearn to be taken to an oasis: a hotel where you can lie down, relax, keep your bags safe, get a drink, get your bearings.

You ask to be taken to a hotel recommended in your guide book, or by a friend, or that you found on the internet. Sorry, that hotel is closed, you’re told. Or it’s full. But lucky for you, the taxi driver knows just the place.

Yeah, right.

It’s a scam. The hotel is not closed. It’s not full. But the place your taxi driver knows will give him a nice kickback. In some places, the scam can get elaborate: they’ll fake calling the hotel, and you’ll be given the phone, informed by the supposed hotel receptionist (actually the scammer’s friend) that there are no more rooms available.

I’ve had plenty of people attempt this scam on me, and know how to avoid it. Glaring at your taxi driver or laughing it off usually do the trick.

So when I arrived in Bamako, Mali, I was not shocked when I was told the hotel was closed. I laughed, and asked again to be taken there. The driver (and a few of his buddies standing around him) insisted that it had closed down.

Fine, I said, take me to this other place instead (I had two potential hotels selected ahead of time), and off we went.

The driver couldn’t find it. Asked for directions. Comically, one guy pointed in one direction and the guy next to him pointed in the complete opposite direction.

I dug up the phone number, and the taxi driver dialed it. He spoke a little bit then handed me the phone. The woman on the other end told me she was the ex-owner and that the hotel was closed.

Give me a break. The taxi driver must have dialed his accomplice instead.

Oh yeah? I asked. What was your hotel’s address before it closed? She said she didn’t remember. Caught you! I thought.

So I reamed into the lady on the other end of the phone, accused her of fraud, threatened to call the police, hung up on her and started laying into the taxi driver for good measure.

I demanded the phone from the driver, and dialed the number to the hotel myself. Same lady. Oops.

Well, as fate would have it, she was indeed the ex-owner and the hotel had closed. As had the other one. The exact two that I had picked. The odds of that happening when selecting out of a newly published guide book are what, zero?

In the process of apologizing, the phone’s outbound minutes expired, so it appeared that I hung up on the same woman twice.

Amazingly, the woman called back, went out of her way to recommend another place, and even called ahead to reserve the room for me. As I ate dinner there that night she did show up to give me a piece of her mind, though. I was thoroughly berated, although I couldn’t help laughing at the absurdity of it.

Sometimes hotels really are closed, and sometimes what looks like a scam really isn’t.

March 1st,2009

Mali |

3 Comments

Bamako, the capital city of Mali, is hot, sunny, and dusty. But by no means lacking in personality.

February 28th,2009

Mali |

No Comments

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

Click to subscribe via RSS feed