I recently received the following email from a reader of this blog:

I recently received the following email from a reader of this blog:

“Maybe your ears were ringing last night, but my husband and I were at a Martyn Joseph concert in Edmonton and Martyn is a World Vision sponsor. After the concert we went to talk to the WV people and decided to take on a little boy, Arafat Ali, from Bangladesh. I was so taken by the pictures and your comments how everyone you met shared whatever they had and invited you in for tea…you never know the impact you are going to have on the world.

Anyway, you have helped to change a young boy’s life…his “occupation” at his tender age of six, is ‘cleaner’…let’s hope that at the very least he will learn how to read.”

Wow. What a wonderful thing to do, and if my travels and writings played even a small part I am truly humbled. But really, the kindness and genuine hospitality that I encountered in Bangladesh were quite extraordinary, and it is heartwarming to see that selflessly reciprocated from halfway around the world.

Good luck, little Arafat!

February 6th,2009

Bangladesh |

1 Comment

James Bond himself made an appearance in Udaipur in the movie Octopussy. The magnificent white Lake Palace in Udaipur’s Lake Pichola was one of the principal settings in the film, as was the Monsoon Palace, home to Bond’s arch-nemesis Kamal Khan.

February 6th,2009

India |

No Comments

A thin slice of Calcutta's massive Howrah train station

India’s train system is a gargantuan marvel, and if you spend any time here, you’re bound to eventually be lured into its web.

The first tracks in India were laid in 1853, with encouragement from the British East India Company. With an eye towards the flow of goods for international trade, most routes in the first 50 years were built heading to one of the three major port cities: Bombay, Madras and Calcutta.

Today, India’s railway system interconnects the entire country. 39,350 miles of tracks and counting. 6,909 railway stations. 18 million passengers per day.

That makes India the world’s 2nd largest transporter of rail passengers annually.

Pascal and I have made our own humble contribution to this impressive statistic. Given the distances between certain cities, when on a tight schedule one of the easiest ways to maximize your time is to sleep on overnight trains instead of hotels.

Of course, what sounds brilliant in theory does have a few strings in practice.

First, although Indian Railways pulls in a neat $18 billion in revenues annually (supporting 1.4 million employees–the largest commercial employer in the world), our budgets for this trip did not include splurges on expensive first-class sleeper berths. Or second class sleeper wagons, for that matter.

Instead, we opted for the more affordable 3rd class sleeper wagons (AC 3-Tier, as they’re known) whenever possible: two sets of 3 bunks facing each other (hence the 3-tier moniker) on one side of the aisle, and 2 bunks on top of each other facing lengthwise on the other side, for a total of 8 open “compartments,” or 64 bunks per wagon.

These are still a step up from the basic common “Sleeper” class wagons which make up the majority of long-distance trains (and most definitely from the regular and crowded wooden bench seat wagons.)

Here are two important things I wish I’d known.

First, never get a top bunk. All three bunk levels are cramped, but heaving yourself up to the top level and attempting to get yourself wedged into a sleeping position involves some moves and acrobatics that should only be reserved for the Kama Sutra. Let’s not even discuss getting down in the middle of the night on a moving train in the dark to find the restroom.

On the top bunk, you’re also furthest from where all the bags are stored under the bottom bunk, so most vulnerable to theft–Pascal and I often ended up sleeping with our bags, which adds a whole new layer of discomfort and contortion. Plus, in the top bunk you’re right under the main light, and nowhere near the light switch. And I mean right under, as in a very bright few inches under.

The second thing I wish I’d known: for the love of God, don’t get a bunk next to the wagon door. The bunks must be 6 feet long. That might be fine for the vast majority of Indians, but at my height of 6’1″ they were just short enough to see my sleeping feet dangle vulnerably off the edge. Right smack where the metal door opens up. There is little quite as ruinous to a good night’s sleep as a metal door repeatedly slamming into an exposed ankle or toe.

But when all is said and done, it’s quite an amazing and mostly comfortable way to travel. Now, the same can’t be said of Sleeper Class, but I’ll get to that later…

February 5th,2009

India |

4 Comments

With its peaceful lakeside setting, flanked by some of the oldest mountains in the world, Udaipur is billed as the most romantic city in India. Indeed, many a wedding and honeymoon have seen the sun set over the “City of Lakes.” But the city is more than just about young love, also featuring some memorable temples, palaces and people.

February 4th,2009

India |

No Comments

The Indian state of Rajasthan

The British called them a martial race. The Rajputs, inhabitants of what today is known as the Rajasthan province of India. Naturally warlike and aggressive in battle.

Today’s Rajputs are descendants of the ancient royal warrior class. They were historically the royal warrior elite and landowning caste (kshatriyas) in northern India, organized into clans under a ruling chief (maharaja). Traditionally, there are 36 royal Rajput clans.

A European equivalent would be the medieval knights of noble blood. Indeed, all of Rajasthan’s main cities resemble the European medieval city states of old, each with an imposing fortress and palace more impressive than the next.

Fierce in battle, Rajput warriors were highly prized in the British armed forces, and to this day occupy a distinguished and disproportionate share of India’s army. Brave, patriotic and bold have been adjectives used to describe them, with a rich tradition of honor and chivalry.

Here’s a famous story from 1303 that helps appreciate the Rajput mindset.

The Sultan of Delhi, Ala-ud-din, heard of the incredible beauty of the new Rajput queen of Chittor, Rani Padmini. Under pretense of being a family relation, he asked her husband, King Ratan Singh, to see her.

Suspecting foul play, Padmini agreed to be seen only via mirror. Stunned by her beauty and instantly infatuated, Ala-ud-din’s men kidnapped the unsuspecting King Ratan Singh, to be released only if Padmini agreed to become his mistress.

Rani Padmini agreed to come out the next morning with 50 servants, and a procession of 150 palaquins (covered carriages) made their way to the sultan’s camp. They were assured that no one would try to peak inside, to preserve the women’s modesty. Instead of Padmini and her retinue, however, these were filled with the king’s best soldiers, who managed to rescue the king from the sultan’s forces and return him to the fort.

The man leading the sneak attack was Gora, Padmini’s uncle. During the rescue, he came within reach of the sultan and could have slain him, but the sultan quickly hid behind one of his concubines, and the Rajput code of honor forbade Gora from harming an innocent woman. He was killed by the sultan’s men.

The furious sultan laid siege to the fort, and after several months it was clear that the situation for the king’s forces was hopeless. The king ordered that he and his men go out for a suicide charge the next day. A final fight to the death rather than face dishonor.

Upon learning of this, Padmini had a large pyre built in one of the fort’s rooms. The morning of the charge, she and all of the palace women, dressed in their finest, leaped into the flames in a final act of self-immolation rather than be taken captive by the sultan.

All the men were killed in battle. All the women died in the fire. But their Rajput story is immortal and recited to this day with pride.

As Pascal and I traveled from Bundi to Udaipur, we passed by the fort of Chittorgarh, where these events happened some 700 years ago, and made our way deeper into the territory of these proud and fearsome warriors.

February 3rd,2009

India |

3 Comments

A continuing exploration of the blue alleys of pretty Bundi…

February 2nd,2009

India |

No Comments

Getting ready to take yet another cold, cold shower, I felt something on my back.

Getting ready to take yet another cold, cold shower, I felt something on my back.

A tick.

Apparently, in all of our skulking around in the weeds, grasses, shrubs and bushes surrounding the Bundi Palace, I picked up an unwelcome guest. Gah.

So of course I did all the wrong things.

I recalled that you can’t just pull a tick out. Their head is wedged inside your skin, pincers tight. Pull too hard, and the body will separate from the head. That kills the tick, of course, but it also leaves the tick’s hair inside, which can easily lead to infection.

[Wrong. Actually, thanks to belated internet research, the best thing to do when you find a tick is to pull it out, as soon as possible. Even if parts of it stay in. That’s because the longer the live tick stays in, the higher your chances of contracting diseases from it. If the head breaks off it can be removed like a splinter, or left in without much issue to come out on its own–it’s the contaminants inside a tick’s body which are a problem and which you do not want secreted inside you.]

I sent Pascal to get matches from the owner of the guest house. The idea is to light a match, extinguish it, and quickly apply the still very hot end to the tick’s backside. The theory is that this panics the tick, and they either pull out on their own or are too stunned to resist when you pull them out. It didn’t work, although Pascal did manage to burn me several times, to much cursing and jumping around.

[The match idea is actually not recommended, as it may cause the singed tick to release potentially contaminated fluids inside you.]

So I went for option two, which is to suffocate the little bugger in alcohol. Then it should be a simple matter to pull it out. Didn’t work.

[Also not recommended, for the same reason as above.]

Cursing the tenacity of Indian ticks, I decided to sleep with it. It looked dead at this point, but I wasn’t sure.

[Definitely not recommended, as the longer the tick stays in, the higher the chances of infection.]

The next morning I checked and it was still there. That’s it. I grabbed my tweezers and pried the blood-sucking bastard out. Then I ate him, just for good measure.

[Finally, the right thing! Well, except for the eating. I just made that up. But it would have been poetic justice, eh?]

February 1st,2009

India |

5 Comments

Bundi is a very blue city. A vast number of houses are painted blue, the color of the Brahmin caste in Hinduism (the highest caste, regardless of level of income). This doesn’t necessarily mean that the people I photographed are Brahmins, but likely the owners of the houses are.

January 31st,2009

India |

No Comments

Uninhabited for over 50 years and home only to monkeys, wasps and bats, the Bundi Palaces are now open for the curious…

January 30th,2009

India |

2 Comments

Be it in India or elsewhere, it is fascinating to see forts and palaces that once represented the pinnacle of wealth, technological achievement and regional pride reduced to crumbling ruins, mere curiosities for visitors, ignored by the locals, and slowly overtaken and reclaimed by nature.

Be it in India or elsewhere, it is fascinating to see forts and palaces that once represented the pinnacle of wealth, technological achievement and regional pride reduced to crumbling ruins, mere curiosities for visitors, ignored by the locals, and slowly overtaken and reclaimed by nature.

India’s large western province of Rajasthan is home to innumerable such sights. Always independently spirited, in the “Wild West” of India it seems you can’t go anywhere without stumbling upon an even more impressive medieval fortification, old palace or simply scores of lavish, beautifully decorated mansions. Of all of these, some are still lived in, some have become museums, and some have been left to slowly wither away and decay unattended.

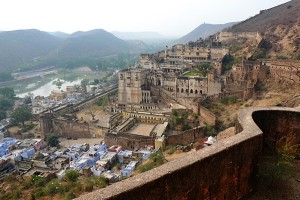

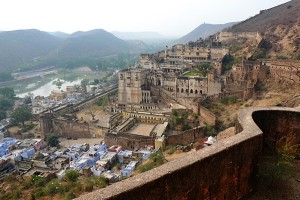

While neither the most well known nor the most impressive of the region, the Bundi Palace in (surprise) the town of Bundi is nevertheless one of the most atmospheric.

It’s not actually a single palace, but an amalgamation of a number of smaller palaces built on top of and around each other, most within the 17th century. These include the Chhatra Mahal, Phool Mahal, Badal Mahal, Umed Mahal and Sheesh Mahal (this is how I learned that Mahal means palace).

This tortured growth of interconnected palaces, the massive fort of Taragarh on the hill above and fortified ramparts surrounding both, the labyrinth of secret tunnels criss-crossing through the hill under these, and the convoluted scenic and man-made artistic beauty of it all prompted Rudyard Kipling, who sojourned in the peaceful setting of Bundi to write Kim, to call it “the work of goblins rather than of men.”

Goblins or no, we thoroughly enjoyed it. Between the beautiful murals in some of the palaces, the open air gardens and pool magically overlooking the whole town, the maze of arches, passageways and pillars, and large wooden doors with metal spikes, the place felt indeed like one of those fairy tale palaces of old. Better yet, because Bundi isn’t a major stop on most tourist itineraries we virtually had the whole place to ourselves.

By late afternoon, we were clearing paths through the underbrush, and scaling several of the ramparts to try to gain access to hidden or blocked off sections of the palaces, earning a running commentary from the nearby monkeys not used to such encroachments into their territory.

In places, there were hives of wasps so huge they defied common sense. When the wasps number not in the thousands but in the tens of thousands, a loud, dark, ominous mass of buzzing, how do those in the middle survive? How do they stay attached to the intricately carved stone arches?

In another, we ventured inside to a black, cavernous chamber. Our eyes adjusting to the darkness, our footsteps light on the dirt floor, the strong smell of something familiar yet which I couldn’t quite place assaulted our nostrils. As our vision cleared and our ears processed the significance of the constant background of high-pitched screeching, we saw that we were surrounded by bats. Bats everywhere. Not just above us in a sea of black but also hanging down to eye level on all the walls in each direction, a mass of black, sightless, twitching creatures resting before their nocturnal escape.

How far the story of these palaces have come. Once the abodes of the mightiest rulers of the land and the luxurious lifestyle of their royally pampered families, now the dominion of troops of monkeys, throbbing hives of wasps, and sleeping quarters of the dreaded and reviled flying rats.

January 29th,2009

India |

9 Comments

I recently received the following email from a reader of this blog:

I recently received the following email from a reader of this blog:

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

Click to subscribe via RSS feed