Some images from Itmad-ud-Daula’s Tomb (the “Baby Taj”) and the palace and mosque at nearby Fatehpur Sikri. Close to Agra and largely overshadowed by the pull of the Taj Mahal, they each nevertheless have a unique beauty all of their own.

January 28th,2009

India |

1 Comment

The Taj Mahal is a tomb. A gigantic, elaborate headstone for a grief-stricken emperor’s favorite wife. Here’s the story.

The Taj Mahal is a tomb. A gigantic, elaborate headstone for a grief-stricken emperor’s favorite wife. Here’s the story.

In the early 16th century, the Muslim emperor Babur, through a series of military conquests, established the Mughal dynasty in India, which lasted all the way until the reign of the British. Babur was a direct descendant of Genghis Khan (through his mother) and of the conqueror Timur (a.k.a. Tamerlane, founder of the Timurid dynasty) through his father.

In 1592 Babur’s great-great-grandson Prince Khurram Shihab-ud-din Muhammad was born, and in 1607 at the tender age of 15 was betrothed to the 14-year old Agra-born daughter of a Persian noble. They would have to wait 5 years until their actual marriage, however, the court astrologers deeming this future date to be more conducive to a happy marriage.

So at a respective 20 and 19 years of age, they were married in 1612, she to become Prince Khurram’s third (and favorite) wife. Entirely besotted with her, Khurram renamed her Mumtaz Mahal (Jewel of the Palace), “finding her in appearance and character elect among all the women of the time.”

It was, by all accounts, a blissfully happy marriage. Mumtaz accompanied her husband everywhere, including his military campaigns, and was his trusted advisor and companion. Prince Khurrian became the fifth Mughal emperor (thereafter known as Shah Jahan) when he successfully fought for the throne in 1628, but unlike many emperor’s wives Mumtaz steered clear of court intrigues and politics. From all accounts, she was beloved of all.

Mumtaz would bear 13 children to Shah Jahan before dying during the birth of her 14th child in 1631. She was 38.

Shah Jahan’s grief at his wife’s death was immense, and immediately he ordered for work to begin on the mausoleum for her grave, the Taj Mahal, to be built in her birth city of Agra.

At a cost in today’s currency of billions of dollars, some 20,000 workers were recruited to work on the project from around the kingdom, from laborers to the most skilled artisans and specialists of the time.

White marble, jasper, jade, crystal, turquoise, lapiz, sapphire, carnelian and scores of other precious and semi-precious stones were imported from such far away places as China, Tibet, Afghanistan, Arabia, Europe and Sri Lanka.

Twelve years later, the tomb was complete, and the gardens, mosque and gateways another ten years after that.

Billed as the world’s greatest monument to love, the Taj sees 2 – 4 million visitors annually and is one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore has described it as “a teardrop on the face of eternity,” while Rudyard Kipling called it “the embodiment of all things pure.”

In his own words, however, here is how Shah Jahan (who would eventually be interred right next to his beloved wife), describes the Taj Mahal:

Should guilty seek asylum here,

Like one pardoned, he becomes free from sin.

Should a sinner make his way to this mansion,

All his past sins are to be washed away.

The sight of this mansion creates sorrowing sighs;

And the sun and the moon shed tears from their eyes.

In this world this edifice has been made;

To display thereby the creator’s glory.

January 27th,2009

India |

7 Comments

Here, Pascal, stand right there...

My brother Pascal joined me in Calcutta for the Indian portion of the trip. Here are his first thoughts:

India has been described to me in different ways. On the one hand the rapid modernization, call centers, businesses, movies and industry spreading throughout the country. And on the other the slums, poverty, beggars, and swarming crowds of such that would make any tourist feel guilty with shame at their own wealth.

My initial extraction from airport-land happened in Calcutta, and during a day’s worth of walking around the entire downtown area I hardly ever came across a single beggar. Even in Varanasi, there were very few beggars and they were more discreet and spiritually oriented. There are definitely huge gaps between the abject poverty levels in some places and the wealthy who live in European-style environments. Overall, though, prosperity has clearly risen, and there are more people walking around with cell phones than scrounging on the streets to stay alive.

Before coming here I was worried about how we would work out transportation and if we would have to hire taxis and guides and so on. It turns out that it was all needless; the rail system here is extremely well-developed and I was impressed by the size and number of people at Calcutta’s Howrah station. Thousands and thousands of people streaming in and out of there every minute, rushing around like massive ocean currents flowing chaotically in different directions.

One of the biggest differences with home is how many scents are drifting through the air all the time. There are all the open-air cooked foods, the incense, flowers, fragrances and so on. I’ve heard that when people leave India they feel like they’ve lost their sense of smell.

Varanasi is one of India’s holiest cities, and the depth of it can certainly be felt. There are stylish building facades, people praying and bathing in the Ganges river. There is a maze of buildings where the streets intertwine like a spiderweb with no center. Some alleys are hardly wider than sidewalks yet somehow find room for cows, carts, and motorcycles.

Every now and then a funeral procession will rush their way through carrying a dead body on a stretcher. The body is covered with fancy cloth, color-coded for age and gender and later burned at a sacred ghat in front of the river. Surprisingly, it doesn’t smell, even a couple dozen feet away from where they burn hundreds of bodies a day. The remains are scattered into the sacred Ganges river, a watery cocktail of feces, sewage, body parts, human ashes, fish and bacteria. Despite this, thousands of visitors come to submerge themselves in the river or drink the water. We’re not sure if Indians are naturally immune to Ganges water or if they regularly get sick.

Back at the Varanasi train station, it’s a return to the bustle of the typical Indian city streets, with aggressive jostling for space by the many bicycles, cars, tuk-tuks, rickshaws, pedestrians, dogs, trucks, buses and cows in between shops and stands of all types and sizes.

January 26th,2009

India |

3 Comments

A day roaming in Vanarasi’s Old City and its bathing ghats on the Ganges river.

January 25th,2009

India |

4 Comments

“Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.”

“Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.”

No, that’s not a line about your grandmother. It’s Mark Twain describing the northern Indian city of Varanasi, also known as Benares or Kashi.

Continually inhabited for over 3,000 years (and with settlements dating back an additional 2,000 before that), not only is Varanasi one of the oldest cities in the world but also one of its most culturally and historically important.

Set on the banks of the Ganges river, Varanasi is one of seven sacred cities in Hinduism, prominently featured in the texts of the Rigveda, Ramayana and Mahabharata, and considered the birthplace of Ayurveda (Vedic medicine). For Hindus, bathing in the holy water of the Ganges at Varanasi is believed to remit sins, especially on holy days, and the city sees over 1 million religious pilgrims annually to bathe in the many ghats (steps leading down to the river).

Hindus also consider that dying in Varanasi is a means to free the soul, and every day sees the burning of hundreds of bodies by the river as part of cremation ceremonies. It is a loud, lively, colorful, otherworldly and altogether unusual sight to see the pyres set out in the open lit day and night as body after body is consecrated to traditional fires.

Varanasi is also the place where, around 500 B.C, the Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara consolidated the monistic Hindu doctrine of Advaita Vedanta, leading to the great Hindu revival. It is from this main branch of Hinduism that Brahmananda Saraswati (aka Guru Dev) emerged, as the Shankaracharya (spiritual head) of Jyotirmath until his death in 1953. Most in the West are familiar with one of his principle devotees, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who toured the world for the latter half of the 20th century teaching the practice of Transcendental Meditation.

Varanasi is also a holy city in Buddhism, one of four designated by Gautama Buddha himself. It is in Varanasi’s residential area of Sarnath that Buddha is said to have given his first sermon on the principles of Buddhism, and the spot where he met his first disciples. The Dalai Lama apparently spends time here as well, and was reportedly in the city on the day that we visited.

As a visitor, the first impression one gets in the Old City is the jumble and tangle of tiny streets and myriad of alleyways going in every which direction. It is next to impossible to keep your bearings as the alleys wind and turn haphazardly, revealing countless little shops, colorful doorways, hidden monuments, small temples, and wandering cows.

And then, a random alley opens up to the Ganges river, and it’s beautiful wide open space, colorful steps leading down to the water, hundreds of little boats, burning funeral pyres, bathing pilgrims, and scenic temple facades and towers overlooking it all. Above all, somehow, a pervading sense of peace and serenity, an ancient city that transcends time itself.

January 24th,2009

India |

2 Comments

Being confronted with abject poverty is not an easy thing, especially coming from the relative riches of a Western society. While the tide for Calcutta, like all of India, is turning, one need not look far to find those still scrounging on next to nothing, and to be simultaneously disturbed, confused and humbled in the process.

January 23rd,2009

India |

1 Comment

There is order amidst the chaos that is India. Just don’t expect it to always make sense.

There is order amidst the chaos that is India. Just don’t expect it to always make sense.

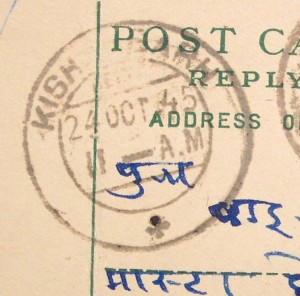

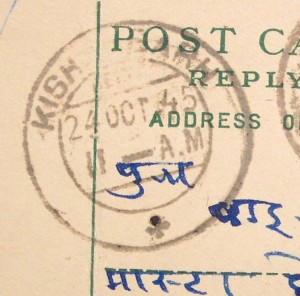

Take sending a letter. Easy enough, right? Ah, if only.

The post office opened at 10:00, and when I got there at 10:37 the doors were just opening. I walked inside, the interior decoration best described as “old style colonial doom-and-gloom,” presented with a row of glaring clerks.

I would like to mail this letter, I said. But they did not have envelopes. An odd oversight, given their reason for being. So out of the post office I went, and found a shop that could sell me an envelope.

I returned and presented my letter. The clerk weighed it, then sent me packing to another clerk down at the end to pay. This surly fellow was in the middle of a heated argument with a customer clear across the hall.

Eventually, he turned his attitude towards me and flipped through a large book of stamps. 181 rupees total postage, so I gave him 201 rupees. First he found a 50 rupee stamp. Then two 20s. Then a 10. This was a slow, laborious process. Then four more 20s. Then a 1.

He then asked for 181 rupees. I gave you 201 already, I said. (Nice try, I thought.) Ah. So he found my 201 rupees. Then was confused about change, so he grabbed the stamps back from me and counted them, with another customer chiming in as well. 181 rupees.

He wrote 181 down on a scrap piece of paper. Then wrote 201 above it, and proceeded to work out the subtraction manually on this piece of paper while I stood there wondering how in the world this man became cashier. Finally, he calculated the change to be 20 rupees. Astounding. Someone give this guy an abacus.

He opened an old metal lock box, fished out two 10s, and waved me off. Uh, what about the letter? I inquired. During all this counting I had tried to lick the back of one of the stamps to paste it on the letter, but there was no adhesive whatsoever on them. He pointed back in the general direction of my original clerk.

I went back to my glaring clerk, letter in one hand and 181 rupees in stamps in the other. You need glue, I was told. Thank you, Sherlock. And no, the post office did not have glue, I was told. Three times, actually, since I couldn’t believe it the first two.

Back out of the post office I went with my envelope and assorted stamps. Have you ever walked around a city asking shopkeepers if you could borrow their glue? Me neither. First time for everything, but eventually I found it.

I now had a complete, stamped letter, which I brought back to my clerk, who had not yet warmed up to me despite this being our fourth encounter. The clerk looked at the letter and said it could not be mailed, because the return address wasn’t in India.

I pointed out that I didn’t live in India. This created a little brouhaha in the post office. Another clerk got involved, then a manager. I have no idea what they were saying because it was all in heated Hindi, but there was pointing (at the letter, at the offending return address, at me, back at the letter) and waving of arms and shaking and waggling of heads. You’d think I’d asked if I could mail firecrackers.

Eventually the manager (the one with the biggest belly) did a sideways head waggle, the clerk stamped the letter through and gave me a final parting glare, and that was that. I had mailed my letter, Indian-style.

January 22nd,2009

India |

10 Comments

Part streets, part alleyways, part shops and part everyday living, Calcutta’s city center is a jumbled maze of Bengali humanity…

January 21st,2009

India |

1 Comment

For many Westerners, Calcutta (now Kolkata) has been synonymous with poverty and Mother Teresa. But there is much more to Calcutta than slums and charity.

For many Westerners, Calcutta (now Kolkata) has been synonymous with poverty and Mother Teresa. But there is much more to Calcutta than slums and charity.

Drugs, for one.

In the early 17th century, the Indian Mughal emperor Jahangir granted the British East India Company the right to build a trading post in Surat (western India) in exchange for goods from European markets. This was soon followed by rights to posts in Madras, Bombay, and in 1690, to the banks of the Hooghly River near a small Bengali village named Kalikata.

The Company built Fort William next to Kalikata in 1702, and the city that grew around it became known as Calcutta. As the Company’s trade in cotton, silk, dyes, saltpetre, tea and spices grew, so did the city.

But it was the rise of the opium trade that truly led to Calcutta’s meteoric rise in prosperity and importance, leading it in 1772 to be named the capital city of British India, encompassing all of today’s India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

After the British wrestled full control of Bengal from the Mughals in 1757, fields of rice were converted to fields of poppy, and Calcutta became the major clearinghouse for the opium trade. From Calcutta the opium was smuggled on British ships to China, feeding a growing demand for the drug, the ships returning with the prized Chinese goods of tea, silk and porcelain.

With the opium trade eventually reaching some 1,400 tons per year, Calcutta flourished, the British prospered, and by the early 19th century Calcutta was known as “The City of Palaces.”

But the high of drugs is not indefinite, and Calcutta also fell victim to the withdrawal pains of the fall of the opium trade (despite two wars with China that Britain fought to maintain it). Delhi took over as the seat of Indian government in the 20th century, and Bombay soon replaced Calcutta as the main commercial hub. To add to its loss, overcrowding, poverty, and Hindu-Muslim religious violence also plagued the city as independent India and Bangladesh were formed.

Today, though, it is a city once again on the rise. Mother Teresa and other relief organizations have brought help and international awareness to the city, but it is its burgeoning IT enterprise that is now rapidly lifting the city into greater prosperity, perhaps one day to reclaim its past glories and accolades. Without the opium high.

January 20th,2009

India |

No Comments

There are many ways to visit a city. Most involve going to designated monuments, attractions, and places of interest. But my favorite is to randomly just start walking, with no destination in mind.

January 19th,2009

India |

3 Comments

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

Click to subscribe via RSS feed