There are two kinds of street photography: what I call permission photography and forgiveness photography.

There are two kinds of street photography: what I call permission photography and forgiveness photography.

In permission photography, which is they type I normally do, you walk up to individuals and groups you meet on the street, establish contact, and gain permission to take their picture. It can take anywhere from 3 seconds to over an hour, depending on the situation and context, but the point is that the subject has given permission to have their picture taken.

There is a level of trust, eye contact, and often some control over the framing and positioning of the shot in permission photography. These are usually plusses. On the downside, the pictures are less spontaneous and can feel posed or static. In physics as in psychology, this is known as the Observer Effect: people often behave differently when they know they are being observed.

And then there is a second type of street photography, what I call forgiveness photography. This simply involves taking pictures before or without the subjects realizing that they are being photographed. Hence, when inevitably some of them do realize you’ve poked a voyeur’s eye into their daily existence, the need to smoothly patch things over with friendliness and reassurance–i.e. the forgiveness.

Forgiveness photography, like photojournalism, often feels more “real” or raw. It’s people in motion versus people stopped.

Given that I’ve been doing about 80/20 permission vs. forgiveness photography so far on this trip, in Calcutta I decided to reverse these. My focus and task, in this city, would be on capturing the immediacy of unposed moments and reality of life unscripted…

January 18th,2009

India |

3 Comments

I quite enjoyed Jessore and its surrounding villages, and spent another day roaming around. I also drank a record number of cups of tea, being constantly invited to sit down and chat, eat biscuits, and meet family. Truly wonderful people.

January 17th,2009

Bangladesh |

2 Comments

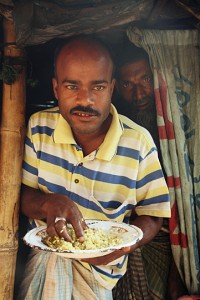

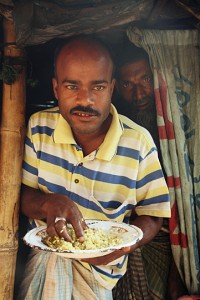

OK, this one should be interesting. Help me write a clever or funny caption for this image, via comments…

January 16th,2009

Bangladesh |

6 Comments

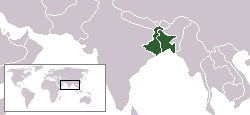

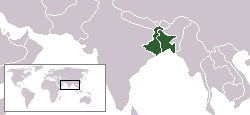

West Bengal (part of India) and East Bengal (Bangladesh)

Someone could be a native of Bengal, speak only Bengali, and yet not be from Bangladesh. In fact, today this describes over 80 million people. Here’s how this happened.

In the beginning there was Bengal, the primarily low-lying area formed by the delta of the Ganges, the largest river delta in the world. Most of the land is within 30 feet of sea level, and the mostly uninhabitable southern portion, the Sundarbans, is dangerous marshy jungle. In addition to the usual snakes, crocodiles, and other predators big and small, the Sundarbans is still home to the feared Royal Bengal Tiger, which to this day kills an average of one person every three days–typically the seasonal honey collectors that live and work at the edges of the lush mangrove forests.

There are recorded settlements in the fertile rice-producing lands of Bengal dating back at least 4,300 years, but it was the 12th century conquest of the land by Muslim Mughal forces that would directly shape its future. The Mughals, whose powerful legacy in India include the Persian-inspired architecture of the Taj Mahal, introduced Islam to the Hindu lands of Bengal, and therein lay the seeds of Bengal’s eventual 20th century split.

By 1947, British India was both on the verge of independence and civil war. Religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims were at an all-time high, included civil unrest, riots and violence, and many on both sides were calling for a partition of the country along religious lines. One notable exception to this school of thinking was Gandhi, who stated:

“My whole soul rebels against the idea that Hinduism and Islam represent two antagonistic cultures and doctrines. To assent to such a doctrine is for me a denial of God.”

Nevertheless, Gandhi’s voice was in the minority, and British India in 1947 was indeed split along religious lines (Gandhi’s assassin shortly thereafter was a Hindu nationalist who believed that Gandhi had appeased Muslims at the expense of Hindus.)

Thus was born Pakistan. If you look at a map of the world today, you will see that Pakistan is to the northwest of India. But at the time of the partition, the large Indian province of Bengal to the east was also cleaved in half. The western half became the Indian province of West Bengal, which continues to this day with Calcutta as its regional capital.

The eastern half of Bengal, separated from Pakistan by over a thousand miles, became Eastern Pakistan. As I mentioned in a previous post, Eastern Pakistan seceded from Pakistan in 1971 and is now Bangladesh.

The religious partition of India into India and Pakistan was not entirely easy nor peaceful. It is estimated that some 7 million Hindis moved from Pakistan to India within months of the partition, and likewise that 7 million Muslims moved to Pakistan from India, with mutual violence and slaughter causing upwards of a million deaths.

Today, the ancient state of Bengal is still cut in two. Bengalis share a common culture, history, language and tradition that dates back thousands of years, but religion has cleaved them apart. India’s West Bengal state is 73% Hindu and 25% Muslim, whereas East Bengal, or the country of Bangladesh, is 90% Muslim and 9% Hindu. Relations between the two countries are friendly, as it was India that helped Bangladesh gain independence from Pakistan, but these are now two peoples on different paths.

So this is the tale of the two Bengalis. For the most part, all Bangladeshis are Bengalis, but not all Bengalis are Bangladeshis.

January 15th,2009

Bangladesh |

6 Comments

Jessore is a small town by Bengali standards: only a million people or so. I spent little time in the city proper, which is as busy and congested as Dhaka, and instead went out walking to some nearby villages…

January 14th,2009

Bangladesh |

1 Comment

A night and a day aboard the Lepcha, one of Bangladesh’s five remaining paddle wheel “Rocket” ships.

January 13th,2009

Bangladesh |

1 Comment

I wasn’t sure how I’d feel about riding the “Rocket,” an orange paddle wheel boat that plies the Bengali riverways from Dhaka to Khulna.

I wasn’t sure how I’d feel about riding the “Rocket,” an orange paddle wheel boat that plies the Bengali riverways from Dhaka to Khulna.

I can’t say that I’m too fond of boats to begin with. Plus in this case, the boat was built in 1938. I mean, this fossil was doing river runs before my grandfather laid eyes on my grandmother, let alone told her how pretty she looked. The boat, from my perspective, was ancient.

And it was an overnight trip. It’s one thing to be awake for this; quite another to entrust your sleep to it.

Ah, but the adventure of it all. Irresistible.

So I bought a ticket. A first-class cabin, no less (if I’m going down, I’m determined to do it in style.) And at 5:30 in the afternoon, my backpack and I made our way through the massive rush-hour congestion of Old Dhaka on the back of a bicycle rickshaw to the river dock of Saderghat, all the more exotic and chaotic by the fading light of dusk.

Through the hustle and bustle of the port, with throngs of passengers, bags, porters and goods all pushing their way on or off boats. Down the wooden plank (yes, an actual plank) and onto the Rocket.

The ship has three classes: the eight first class cabins are in the front of the ship, cabin doors opening inside to a central dining / lounge area, and include access to the front deck as well as to separate first-class toilets (relatively speaking). Six second class cabins are in the rear of the ship, cabin doors opening to the outside, and have their own toilets as well (but no dining/lounge).

Then there’s deck class. There are two levels of plain deck, where hundreds of passengers crowd together on blankets and bags and spend the journey on the ship’s floor, carving out whatever amount of space they can wherever they can find it (without crossing into either first or second class areas). Walking around, I saw people jammed together and sleeping in every which corner, including in the dark, damp and unnaturally loud halls of the engine room. As for toilets…you do not want to go anywhere near the deck class toilets.

It is difficult to describe the journey. Beautifully haunting was the departure, paddling past the ghostly ship-breaking yards by moonlight, the Rocket blowing its horn to warn smaller boats of its approach and its lone searchlight occasionally switched on to scan ahead through the light river mist.

By moonlight we traveled, the ship minimizing the use of external lights in order to preserve the pilot’s night vision. Seeing the shapes of the buildings and factories on the shore by twilight, soon replaced by the dark foliage of jungle.

In some places the river opened up so wide that neither shore could be seen, creating a sensation of paddling on into dark infinity. In others, tiny little wooden boats with solitary lanterns atop their canopy slowly parted at our approach, like fireflies languidly drifting to either side in the wind, fishermen working by night to earn their living.

When I could stay awake no longer, I quickly fell asleep to the rhythmic chugging sound and vibration of the paddles, the calm river offering surprisingly little rocking motion.

Dawn came through the fog, softening the scenery and landscape to a magical, mystical land of white. In patches, the fog became too dense to continue, and the paddles stopped, the ship slowly coasting forward in a silent slide in a timeless sea of white. Then a tree in the distance would be glimpsed, almost a dream, then another, and eventually enough of an outline of the banks to start the engines again and continue on.

On the forward observation deck, the waiter brought a hot cup of milk tea, the delicious hot liquid countering the foggy river’s early morning chill, and as I sipped and leaned out on the railing to observe the shrouded riverways ahead, I pondered on all the amazing beautiful things in this world kept secret.

A magical journey. And over almost before it began, the hours passed in the blink of an eye. Seventy one years this ship has been prowling these river waters, and I sincerely hope that others will have the good fortune to savor such an experience in another seventy one.

January 12th,2009

Bangladesh |

5 Comments

The Buriganga River cuts through the southern portion of Dhaka. Along its banks, past the shipyards and docks, are heavily crowded residential areas, from the simply poor to the sweltering corrugated metal shacks of the city’s slums.

While some of these areas were safer than others, it was in these neighborhoods that I met some of the most remarkable people in Dhaka, and was once again humbled by their tremendous good will and hospitality.

January 11th,2009

Bangladesh |

3 Comments

If you can know a city through its people, then here, via portraits, is a very small glimpse into the soul of Dhaka:

January 10th,2009

Bangladesh |

9 Comments

Bangladesh has not had it easy.

Bangladesh has not had it easy.

The people of Bangladesh will be quick to tell you that theirs is a poor country. By purely economic standards, this is largely correct. As the world’s 7th most populous country, average annual income is only $1,400 per person, or half that of neighboring India’s. It is the most densely populated country on earth, with some 150 million people packed into a country the size of the state of Iowa or Greece (or, to view it another way, the same population as Russia packed into 1/120th the land area).

Once part of British India, Bangladesh became part of Muslim Pakistan in 1947 when India gained independence and was split along religious lines. In 1971, isolated from mainland Pakistan with India in between and with political rifts mirroring their physical distance, Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) seceded from Pakistan at a cost of several million lives.

To further round out recent miseries, Bangladesh has also been host to a number of devastating natural disasters, such as flooding in 1998 that affected 2/3 of the country and made some 30 million people homeless, and the world’s deadliest cyclone on record in 1970 which killed upwards of a million people.

Yet for all its difficult recent history and relative lack of prosperity, Bangladesh is superbly rich in culture and hospitality. The amazing friendliness and welcoming spirit of the Bengalis that I met were simply unparalleled. From the poorest residents in the slums of Dhaka to fellow first-class passengers on long-distance riverboats, Bengali natives expressed a genuinely friendly spirit and desire to share the true wonders of their country with the rare tourist in their midst.

Warm handshakes, polite introductions, typically followed by a barrage of questions: where are you from? How do you like our country? Have you seen this or that attraction? Where are you going now? How long are you staying in Bangladesh? And so on, almost universally concurrent with or followed by an invitation to drink tea, visit their home, and meet more of their friends and family.

Whatever natural and historical attractions the country may have (and it certainly has its share of both), it is truly Bangladesh’s people that make the most lasting impression. As the country’s economy continues to improve, one can envision and hope for a Bangladeshi future where its material riches soon catch up to its interpersonal ones.

January 9th,2009

Bangladesh |

3 Comments

There are two kinds of street photography: what I call permission photography and forgiveness photography.

There are two kinds of street photography: what I call permission photography and forgiveness photography.

Click to subscribe via RSS feed

Click to subscribe via RSS feed